The experience

"In this story you’ll experience the front seat thrills of bush planes and helicopters operating in the most dangerous conditions on earth - in Alaska. Opens with an interesting early history of the 49th State, leading to the eventual use and development of a new tool of transport – the single engine airplane, but not without extracting a terrible price. The author relates his true-life experiences growing up in the territory as a youth and in his flying years. Concludes with an encounter that will compel every reader to grapple with its final truth. A must read for every pilot considering flying in or to Alaska with the included flight safety Appendix and useful links included.

Mark Rose worked professionally in Alaska aviation for many years. As both a pilot and A&P technician, he managed helicopter operations building the 28 mountain communication sites for the Alaska Pipeline, a 3 year 24/7 endeavor, as well as outfitting Arctic hunting expeditions. His experiences in Alaska convinced him that the crust of the Earth had gone through a revolution which aligns fully with the Biblical account of Noah’s Flood, motivating him to author the popular title The Noah Code in 2015 with subsequent editions.

Excerpt:

Chapter 6

Long Hunters

"A light breeze was blowing down the Great Arctic River. All across the plain stretching out to the Brooks Range the rust colored ground cover weaved along, contrasted by fingers of dark green spruce that made a beautiful quilt-work across the valley. Beyond the plain the grey peaks of the Brooks loomed up, pushing higher and higher in an endless maze stretching off past the horizon. A dusting of snow swept their north flanks, telltale of fall. Yellow willow leaves floated down close by with a rustling sound in the breeze, piling among the white roots and grey rocks jutting out here and there along the banks of the river at my feet. That was the only sound that broke the silence, the silence of the Arctic, heard and understood only by those who experience it. The sweet smell of softwoods was also in the air, just as it had been for 20 centuries of falls gone by. It was a painting with a crystal river running through it—this is fall in the Arctic and there is nothing like it in the world.

The machine sat silent on the gravel bar of the river, her wings tied to logs under rock piles, this to keep her from flipping over in a big gust. A gust of 40 will lift a 1000 pounds per wing you see, and more than one pilot has returned to find his ship wrong side up while off on the hunt in this country. But that’s the way it is here, there being no room for error, that is, error between man and machine against the elements, the elements ever winning and teaching another lesson….

I set up flat and level above the trees for another look and pass, so it's mark; ONE, TWO, THREE, FO … the second hand ticks off, "this one’s tight with no wind," I say aloud, but once I get on no sweat I think, I'll be going out light and this exit is perfect. (A fly by @ 60mph is about 100 feet-per-second—for example, 3 seconds makes for a 300 foot strip.) Full power and the cabin comes to life again, the engine pulling me around with a G right by the moosey lake. They’re watching the action out the corner of their eyes now, not stopping to dip for the next mouthful of bottom growth. The lake water is calm. Too bad I think, I could use a breeze. It’s smart to make at least two passes like this when taking on a new LZ, three is better. I lineup on the gap in the spruce that exposes the fan, seeing the water dripping from the bulls’ noses as I race by them mirrored on the lake and making ripples around their legs. It seems they’re thinking, "this guy's crazy, should be a nice crash today!" They are mostly right—wouldn’t be the first time big game in Alaska watched a good wreck! The approach feels good as the river flashes under me, outside-airspeed-outside-airspeed, but she settles under the big load of gas! FULL POWER!! The ship touches down 3 point and I react; POWER OFF, FLAPS UP, BRAKES! BRAKES!! She bounces hard over the first boulders, bigger than I thought as I roll over a few more to a stop. The snag is now sitting but 30 feet in front of my swinging prop and softly idling six, like I was parked at International Airport. I'm shaking a bit, so I take a breath and think "OK…I'm here, fuel stash is set!”

Chapter 8

Over the years, I’ve found that beautiful country often equals finding game. With the initial shock past and still absorbed in the grandeur of the country, I scanned out to the north and left. A broad treeless valley swept over the horizon, providing passage to the summer grounds of the hundred thousand-square-mile North Slope. A motion caught my eye; the ground seemed to be moving. I refocused to make sure I wasn’t seeing an illusion. The entire plain was moving! “It’s the Arctic Herd!” Mick exclaimed. The spectacle instantly electrified the cabin. “Wow! Have you ever seen anything like it?”

No camera or canvas could capture the scene unfolding before us. We were at exactly the right place at exactly the right time to witness this once-a-year event. This was the Arctic Herd in full motion in its annual move from the summer to winter grounds, all in this setting of abject beauty and wonder. What an amazing sight it was! Keeping a wide birth to not disrupt the animals, we toured for twenty minutes as they kept coming and coming. On a remote hillside, we noticed a group we were sure were bulls. As we got closer, other males among the bands became apparent, but these boys stood out. We came to the realization that these monsters were the lead bulls of the entire Arctic Herd. They were watching the grand progression of their wards passing by! Their massive racks stuck up like trees in the treeless tundra. Stunned by it all and regaining our thoughts, it was time to get down to business. Looking south, I saw what looked to be a good landing spot near their path.

"This is too good to be true," I thought. I was soon to find out it was.

Appendix

Alaskan Aviation: An Expert Report

It is of note that many of these efforts have focused on Alaska, where aviation is the primary mode of transportation. Alaska is known for its varied and often unique landscape and when this is considered with temperamental weather and seasonal lighting conditions, even the most experienced pilot would have to agree that Alaskan aviation represents some of the most difficult flying in the U.S., if not the world. The combination of factors mentioned above, the number of GA accidents that are occurring in Alaska and the FAA’s accident reduction were factors in our decision to implement this study.

The Seven Rules of Safe Pass Flying

Most pilots lack the experience or training to fly in severe mountain conditions. The FAA offers little information as part of its training curriculum regarding such. In the mountains, you don’t get a second chance if you fail the practical! Here’s a procedure for how to stay safe and confident flying a pass situation in Alaska or anywhere. Read in entirety:

#1: Know the pass altitude. Study and have the sectional on your knee/screen and then plan to set up your flight path entering the pass on the right-hand side.

#2: Always enter the canyon at pass altitude plus a safety factor. The FAA recommends 1,000 ft. You should be at maneuvering speed, straight and level, which is 80 or 90 in most light singles and maybe one notch of flaps. Why the right side? This so you are in the most advantageous visual position to safely conduct a left-hand 180-degree turn to exit if required.

#3: Never take on a pass crossing in approaching weather—and always have a mile of visibility. A mile is 30 seconds of flight at 120 mph or 45 seconds at 90 mph. Estimate this on your way in. Now, look up ahead and plan a 180 degree turn at your decision point “clear of clouds” location, that place having forward visibility and cloudless across the entire width of the canyon. Note: the decision point must allow a safe turn (30 degree maximum bank) to get across safely. Don’t bust the FARs in a pass.

“Clear of clouds” means clear of clouds! Keep your eye on the airspeed. If there is turbulence, reject the attempt.

#4: Make the decision turn like you are on a Sunday afternoon sightseeing trip with mother onboard. Period. Why fly in stress? The turn is to be executed in two 90 degree segments. Don’t let the terrain or clouds determine your flight path. You control the flight path. Watch your airspeed. The tendency is to pull back to climb over—don’t attempt it!

#5: Again, never take on a pass in approaching weather (such as if a front is passing). It’s always best to allow a front to transit before you try a pass crossing. This will prevent losing your “out” and potentially getting trapped in the area. (I’ve known pilots who have had to execute a “controlled crash” in such a situation.) This maneuver involves an uphill stall into a brushy hillside to soften impact—not to mention some very lousy sleeping arrangement’s while awaiting rescue!

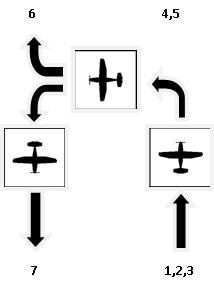

#6: Once you are in your comfortable Sunday afternoon turn—safe and clear of clouds at the halfway point in the canyon (see charts 4 and 5)—level your wings and look out your right side at the “pass.” If you can see through, make a simple RH 90 degree turn[A3] , open to full power, and go for it. If you can’t see through, roll left, continue your final 90 degrees of the 180 degree LH turn, and get out of there. Go back to the coffee shop, hangar, lodge, gravel field, town, village, city, or wherever you wish—land and enjoy another day - alive.

#7: In the rejection turn, you should have some air between you and the ground. A shallow dive to cruise speed may be in order. Except that today was just not a pass day.

Mark Rose worked professionally in Alaska aviation for many years. As both a pilot and A&P technician, he managed helicopter operations building the 28 mountain communication sites for the Alaska Pipeline, a 3 year 24/7 endeavor, as well as outfitting Arctic hunting expeditions. His experiences in Alaska convinced him that the crust of the Earth had gone through a revolution which aligns fully with the Biblical account of Noah’s Flood, motivating him to author the popular title The Noah Code in 2015 with subsequent editions.

Excerpt:

Chapter 6

Long Hunters

"A light breeze was blowing down the Great Arctic River. All across the plain stretching out to the Brooks Range the rust colored ground cover weaved along, contrasted by fingers of dark green spruce that made a beautiful quilt-work across the valley. Beyond the plain the grey peaks of the Brooks loomed up, pushing higher and higher in an endless maze stretching off past the horizon. A dusting of snow swept their north flanks, telltale of fall. Yellow willow leaves floated down close by with a rustling sound in the breeze, piling among the white roots and grey rocks jutting out here and there along the banks of the river at my feet. That was the only sound that broke the silence, the silence of the Arctic, heard and understood only by those who experience it. The sweet smell of softwoods was also in the air, just as it had been for 20 centuries of falls gone by. It was a painting with a crystal river running through it—this is fall in the Arctic and there is nothing like it in the world.

The machine sat silent on the gravel bar of the river, her wings tied to logs under rock piles, this to keep her from flipping over in a big gust. A gust of 40 will lift a 1000 pounds per wing you see, and more than one pilot has returned to find his ship wrong side up while off on the hunt in this country. But that’s the way it is here, there being no room for error, that is, error between man and machine against the elements, the elements ever winning and teaching another lesson….

I set up flat and level above the trees for another look and pass, so it's mark; ONE, TWO, THREE, FO … the second hand ticks off, "this one’s tight with no wind," I say aloud, but once I get on no sweat I think, I'll be going out light and this exit is perfect. (A fly by @ 60mph is about 100 feet-per-second—for example, 3 seconds makes for a 300 foot strip.) Full power and the cabin comes to life again, the engine pulling me around with a G right by the moosey lake. They’re watching the action out the corner of their eyes now, not stopping to dip for the next mouthful of bottom growth. The lake water is calm. Too bad I think, I could use a breeze. It’s smart to make at least two passes like this when taking on a new LZ, three is better. I lineup on the gap in the spruce that exposes the fan, seeing the water dripping from the bulls’ noses as I race by them mirrored on the lake and making ripples around their legs. It seems they’re thinking, "this guy's crazy, should be a nice crash today!" They are mostly right—wouldn’t be the first time big game in Alaska watched a good wreck! The approach feels good as the river flashes under me, outside-airspeed-outside-airspeed, but she settles under the big load of gas! FULL POWER!! The ship touches down 3 point and I react; POWER OFF, FLAPS UP, BRAKES! BRAKES!! She bounces hard over the first boulders, bigger than I thought as I roll over a few more to a stop. The snag is now sitting but 30 feet in front of my swinging prop and softly idling six, like I was parked at International Airport. I'm shaking a bit, so I take a breath and think "OK…I'm here, fuel stash is set!”

Chapter 8

Over the years, I’ve found that beautiful country often equals finding game. With the initial shock past and still absorbed in the grandeur of the country, I scanned out to the north and left. A broad treeless valley swept over the horizon, providing passage to the summer grounds of the hundred thousand-square-mile North Slope. A motion caught my eye; the ground seemed to be moving. I refocused to make sure I wasn’t seeing an illusion. The entire plain was moving! “It’s the Arctic Herd!” Mick exclaimed. The spectacle instantly electrified the cabin. “Wow! Have you ever seen anything like it?”

No camera or canvas could capture the scene unfolding before us. We were at exactly the right place at exactly the right time to witness this once-a-year event. This was the Arctic Herd in full motion in its annual move from the summer to winter grounds, all in this setting of abject beauty and wonder. What an amazing sight it was! Keeping a wide birth to not disrupt the animals, we toured for twenty minutes as they kept coming and coming. On a remote hillside, we noticed a group we were sure were bulls. As we got closer, other males among the bands became apparent, but these boys stood out. We came to the realization that these monsters were the lead bulls of the entire Arctic Herd. They were watching the grand progression of their wards passing by! Their massive racks stuck up like trees in the treeless tundra. Stunned by it all and regaining our thoughts, it was time to get down to business. Looking south, I saw what looked to be a good landing spot near their path.

"This is too good to be true," I thought. I was soon to find out it was.

Appendix

Alaskan Aviation: An Expert Report

It is of note that many of these efforts have focused on Alaska, where aviation is the primary mode of transportation. Alaska is known for its varied and often unique landscape and when this is considered with temperamental weather and seasonal lighting conditions, even the most experienced pilot would have to agree that Alaskan aviation represents some of the most difficult flying in the U.S., if not the world. The combination of factors mentioned above, the number of GA accidents that are occurring in Alaska and the FAA’s accident reduction were factors in our decision to implement this study.

The Seven Rules of Safe Pass Flying

Most pilots lack the experience or training to fly in severe mountain conditions. The FAA offers little information as part of its training curriculum regarding such. In the mountains, you don’t get a second chance if you fail the practical! Here’s a procedure for how to stay safe and confident flying a pass situation in Alaska or anywhere. Read in entirety:

#1: Know the pass altitude. Study and have the sectional on your knee/screen and then plan to set up your flight path entering the pass on the right-hand side.

#2: Always enter the canyon at pass altitude plus a safety factor. The FAA recommends 1,000 ft. You should be at maneuvering speed, straight and level, which is 80 or 90 in most light singles and maybe one notch of flaps. Why the right side? This so you are in the most advantageous visual position to safely conduct a left-hand 180-degree turn to exit if required.

#3: Never take on a pass crossing in approaching weather—and always have a mile of visibility. A mile is 30 seconds of flight at 120 mph or 45 seconds at 90 mph. Estimate this on your way in. Now, look up ahead and plan a 180 degree turn at your decision point “clear of clouds” location, that place having forward visibility and cloudless across the entire width of the canyon. Note: the decision point must allow a safe turn (30 degree maximum bank) to get across safely. Don’t bust the FARs in a pass.

“Clear of clouds” means clear of clouds! Keep your eye on the airspeed. If there is turbulence, reject the attempt.

#4: Make the decision turn like you are on a Sunday afternoon sightseeing trip with mother onboard. Period. Why fly in stress? The turn is to be executed in two 90 degree segments. Don’t let the terrain or clouds determine your flight path. You control the flight path. Watch your airspeed. The tendency is to pull back to climb over—don’t attempt it!

#5: Again, never take on a pass in approaching weather (such as if a front is passing). It’s always best to allow a front to transit before you try a pass crossing. This will prevent losing your “out” and potentially getting trapped in the area. (I’ve known pilots who have had to execute a “controlled crash” in such a situation.) This maneuver involves an uphill stall into a brushy hillside to soften impact—not to mention some very lousy sleeping arrangement’s while awaiting rescue!

#6: Once you are in your comfortable Sunday afternoon turn—safe and clear of clouds at the halfway point in the canyon (see charts 4 and 5)—level your wings and look out your right side at the “pass.” If you can see through, make a simple RH 90 degree turn[A3] , open to full power, and go for it. If you can’t see through, roll left, continue your final 90 degrees of the 180 degree LH turn, and get out of there. Go back to the coffee shop, hangar, lodge, gravel field, town, village, city, or wherever you wish—land and enjoy another day - alive.

#7: In the rejection turn, you should have some air between you and the ground. A shallow dive to cruise speed may be in order. Except that today was just not a pass day.

Scud Running From the AIM FAA publication Airmans Risk Management manual

Scud running, or continued VFR flight into instrument flight rules (IFR) conditions, pushes the pilot and aircraft capabilities to the limit when the pilot tries to make visual contact with the terrain. This is one of the most dangerous things a pilot can do and illustrates how poor ADM (good decision making) links directly to a human factor that leads to an accident. A number of instrument-rated pilots die scud running while operating VFR. Scud running is seldom successful, as can be seen in the following accident report: A Cessna 172C, piloted by a commercial pilot, was substantially damaged when it struck several trees during a precautionary landing on a road. Instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) prevailed at the time of the accident. The personal cross-country flight was being conducted without a flight plan.

The pilot had purchased the airplane in Arkansas and was ferrying it to his fixed base operation (FBO) in Utah. Enroute stops were made and prior to departing the last stop, the pilot, in a hurry and not wanting to walk back to the FBO to call Flight Service, discussed the weather with a friend who told the pilot that the weather was clear to the north. Poor weather conditions prevented him from landing at his original destination, so the pilot turned around and landed at a privately owned airport with no service facilities. Shortly thereafter, the pilot took off again and looped north toward his destination. The “weather got bad” and the pilot decided to make a precautionary landing on a snow-covered road. The road came to a “T” and the airplane slid off the end. The left wing and propeller struck the ground and the right wing struck a tree.

As discussed throughout this handbook, this accident was the result of a chain of poor decisions. The pilot recalled what he should have done in this situation: “I should have picked a spot to do a precautionary landing sooner before the weather got bad. Second, I should have called Flight Service to get a weather briefing instead of discussing it with a friend on the ramp.”

Get-There-It is

In get-there-itis, personal or external pressure clouds good judgment by causing a fixation on the original goal or destination with a foolish disregard for safety and a safe alternative course of action.

Continuing VFR into IMC

Continuing VFR into IMC often leads to spatial disorientation or collision with ground/obstacles. It is even more dangerous when the pilot is not instrument rated or current. The FAA and NTSB have studied the problem extensively with the goal of reducing this type of accident. Weather-related accidents, particularly those associated with VFR flight into IMC, continue to be a threat to GA safety because 80 percent of the VFR-IMC accidents resulted in a fatality.

Link to the 2016 version of the Risk Management Handbook (as of April 2017):

https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/media/risk_management_hb_change_1.pdf

Link to library of free FAA materials:

https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/